Nearly two years after the launch of the MapSwipe app in July 2016, a massive 23,828 people have swiped through its satellite imagery, identifying squares containing buildings and/or roads. Together they’ve swiped 495,135 km2 - that’s very nearly the size of Spain.

MapSwipers are a truly international bunch, hailing as much from Tanzania, Denmark, Singapore or the Czech Republic as from the US and UK.

The app is being maintained by an equally international bunch of volunteers and staff from the Missing Maps community. And thanks to the hard work of volunteers, the MapSwipe app is now open source, so anyone with the relevant coding skills can access the code on Github and help to improve the app. Get in touch if you’re interested - particularly if you have React Native, Python, Firebase or general mobile app development skills!

When you’re lounging on the sofa swiping serenely over a remote part of the planet, it can be difficult to imagine how the data you’re producing is being used or who it’s helping. So I talked to Nell Gray, a qualitative research officer at MSF, about how they’re using MapSwipe data in a project in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

In 2015 MSF opened the Pran Men’m (“Take My Hand”) clinic, which provides medical, psychological and social care for survivors of sexual violence. Nell explains: “Services available for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, especially for minors, aren’t sufficient in Port-au-Prince.” Between May 2015 and Dec 2017 the clinic treated nearly 2,000 survivors, mostly women and girls, and 58% were minors (under 18). It was moving to hear Nell talk about the project; you can read stories here from some of the women and girls who have used the clinic.

“It’s a hugely capable and professional team providing care 24 hours a day to anybody who needs it, often in quite difficult cases. I was just really impressed by them and the work that they’re doing and the huge impact you can have on the lives of people experiencing sexual violence.” Rape survivors should be seen within 72 hours in order to receive effective HIV prevention and emergency contraception. Abortion is illegal in Haiti and although following intensive efforts HIV rates are falling they are still some of the highest outside Africa so the stakes are high for women.

Nell explained that in a large capital city one clinic isn’t accessible to everyone, so there are several outreach sites and MSF are currently carrying out a household survey to look at how they can increase access to services, particularly within the 72 hour window.

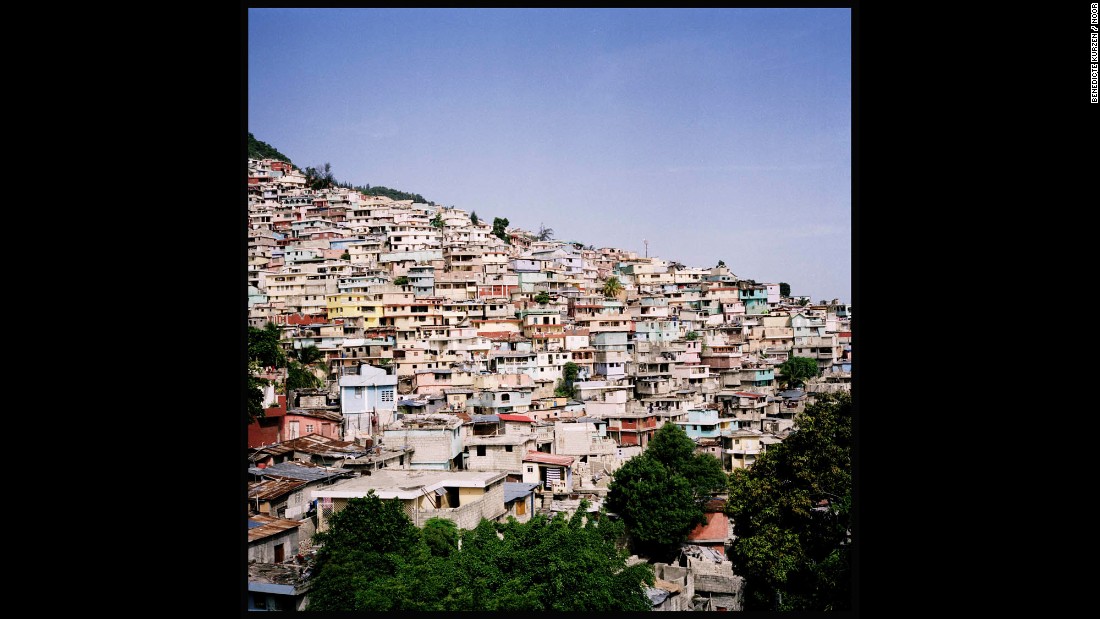

Parts of Port-au-Prince are densely populated, Photo: Benedicte Kurzen/Noor

“We needed to pick random points to do the household survey to ensure the coverage of the survey is good. But the problem with Port-au-Prince is that some places are super densely populated and in some places you could drop a point and there’s no houses there at all. So we were grappling with how to manage that and it was at this point that somebody suggested MapSwipe. Within a couple of days it was done and the field team were super impressed and very happy at being able to work with that data rather than just a blank map of the city effectively.” You can see the MapSwipe data for the Haiti project here.

“We’re not asking about personal experiences or collecting information about incidence of sexual violence, it’s much more about understanding barriers to accessing care or support and how they can be overcome… There is often a question of whether it’s a knowledge issue, so that people aren’t aware that it’s a medical emergency for example or that there are health services available. Do people know about the 72 hour window? Or do they know that and it’s other barriers that stop them coming?”

The survey is also looking at whether particular groups of people or areas are more vulnerable. Because some of the factors may be geographical, having a good geographical starting point is important.

The results of the survey will help MSF carry out a participatory design process with local residents on improving access to services. “That could be anything from different health promotion strategies, different communication messages, different ways of communicating with people, to having services in different places and it would really help us to understand if knowledge is particularly low in an area and we need to focus awareness raising there, or if there are areas where services are particularly inaccessible where maybe we need to work with the Ministry of Health to build capacity in a hospital for example.”

The Haiti project used MapSwipe data directly. But on many projects - and this was its original purpose - MapSwipe is the first stage in preparing more detailed maps as it hugely cuts down the amount of time mappers have to spend scrolling through empty forest and scrub. Detailed mapping is mostly done by volunteers and anyone can get involved - find out how here. There may be a mapathon in your area you can go along to to help you get started.

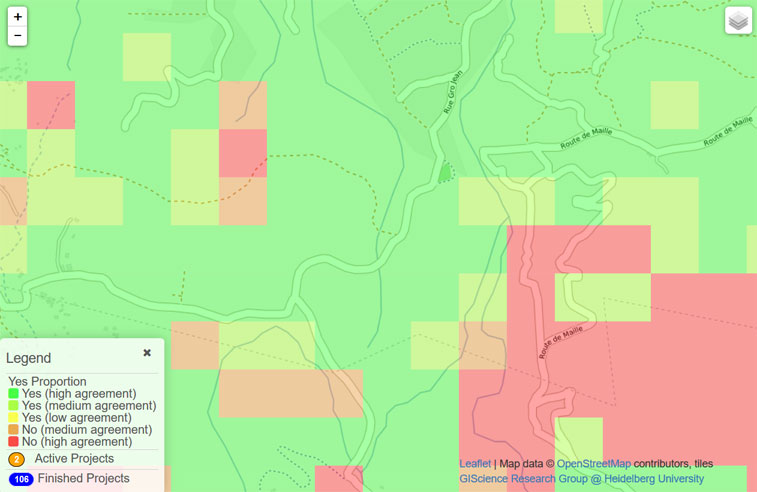

You may be interested in the MapSwipe Analytics website, produced by the Heidelberg Institute for Geoinformation Technology. Here you can see the data visualised on a map or against the satellite imagery, download it to explore it yourself, watch results being submitted in real time or work through a tutorial.

Talking to humanitarian professionals revealed it was important to make the data as open and available as possible so anyone can refer to it when needed, without specialist equipment. So if you look at a project online you can see at a glance where the areas of likely population are. That could be pretty useful in an emergency.

Part of the Haiti project as visualised on the MapSwipe Analytics website: green areas have been marked by MapSwipe users as populated, yet you can see these buildings are not on the base map.

There is an ongoing question whether machine learning could replace MapSwipe, but so far the answer is “not yet”. Researchers at Heidelberg have recently made significant progress but building styles and landscape appearance can vary hugely between different areas so there isn’t a one off solution. MapSwipe data makes great training data sets for these experiments though.

Now the code is open source there’s more opportunity to improve the app and we’ve been keeping an eye on feedback. For instance, lots of people have asked for the zoom function to be more stable, and for it to be clearer what scale the imagery is, so hopefully we can tackle some of these issues.

But what about MapSwipe 2.0? How could the app take a whole leap forward? One suggestion is that it could be used for a complete mapping process - I knocked up a quick prototype for this idea. Or should the user be able to indicate how many buildings are in a square, to give a better idea of population density? Or could MapSwipe be used to indicate where OpenStreetMap and the satellite imagery differ? These are just a few suggestions - let us know if you have more. We’re also looking for funding opportunities. You can get in touch with us via the feedback form (also accessible from the app).

Meanwhile I for one am going to keep swiping - as well as being relaxing and quite addictive as a process it really does make a difference on the ground. I’ve always liked the MapSwipe icon of a person waving as though saying “here I am, please put me on the map”. By putting on the map people like the women and girls who might need the services of Pran Men’m we can help make sure they get the help they need when they need it.

Nell added “I’d also add a huge thank you to all the MapSwipers. The team in the field didn’t realise that MapSwipe was an option. I was explaining it to them and they were just blown away that people were giving their time and energy to help the project and were even more blown away by the fact that it was super quick and effective. It was really hugely appreciated.”